Behind the Poet’s Pen: Kathryn H. Ross on Writing “For My Sake”

by Kathryn H. Ross

Image Credit: from GoldScriptCo.com

A Letter from the Editor

Dear Reader,

Some words just come at the right time, and this is what I found in Kathryn’s urgent, stretching essay on her powerful poem “For My Sake,” which was first published by the incomparable Ekstasis Magazine with Christianity Today. I think I echo the chorus of many of my fellow brothers and sisters in the faith—no matter where your politics might fall—that we are immensely grieved for our country and the increased division and violence we are witnessing here and around the world.

Here, at The Way Back to Ourselves, we are committed to unity, healing, faith, and reconciliation in every way we can possibly find earthside. We believe this is the heart of Christ, and that following his CALL and SPIRIT trumps everything else. For that reason, we do not seek to be political or politically biased, but rather seek to take the 30,000-foot view as believers who want to call all kinds of people of every walk of life into a relationship with God and wholeness.

We seek diversity over divisiveness, truth over trends, love over loudspeakers, and mercy over “Me first!”

Simply put, we yearn to be different in this world of noise and make a home for each soul that Christ calls his own.

We also do not want to avoid difficult topics because it’s easy and safe to do so—just like Christ did not avoid the hard topics of his day. So, in an election year, where we are fully aware that tensions are on the rise, we warmly invite you—all of you—to engage with one another in love, respect, and graciousness—even when we don’t agree. You may find we have more in common with our supposed “adversaries” than we think.

This engagement is the spirit of Kathryn’s essay and poem “For My Sake.” They are written for “such a time as this,” as her words invite us into Kathryn’s own experiences through political division, the pandemic, and the increased violence of the modern age. In the turmoil, her heart and spirit are grieved. In the end, she asks, “How is THIS happening?”

The answer?

Well, you’ll have to read her poem and essay to find out.

It’s our earnest prayer that Kathryn’s words, which she has poured out here like an intimate journal entry, cause us all to pause and ask ourselves, “How am I loving my neighbor and what am I willing to give up to better follow Christ—not just for his sake, but for mine?”

As always, thank you for being here, friend—and especially so when we wade into the deep.

You belong here,

Kimberly Phinney

founder + editor-in-chief

For My Sake

Kathryn H. Ross

I’ve been white knuckling my faith.

The truth escapes me again and again and

I must be retaught—my being a blank

slate wiped clean by the damp warmth

of a rag held under a spigot then

wrung just dry enough to not drip.

I don’t know if God speaks to me anymore,

or if the words I think I hear come from my own mind;

phantom comforts for my yearning.

I don’t know if God speaks to us anymore,

or if the silence is only because

he said it all when it was finished.

He could talk about how

we abuse him in our search

for meaning; how we abuse ourselves

when meaning refuses to be found.

About how the great king said

all is vanity, vanity…

but I don’t want vanity. I only

want you.

So, I lie in bed listening;

nagged by worry that I have only ever

chased after an indifferent wind. Stubborn,

I try to stop my mind from wandering, from

wondering. If I can just

focus, I’ll hear.

But the room is silent and my heart

is full of whispers I cannot discern.

People die for no good reason.

Choose your favorite metaphor:

candles snuffed by a cold wind. Strings

cut by the scissors of fate. A clock that

winds down until its hands are frozen

at the time of death. However

you say it, how do you say it?

They are gone and everything they were is

now not.

Blessed are the crushed poor-hearted who are

broken in spirit, for you promise to be

as close as you were in the secret place

before we began. Lord, will you

begin again?

I feel there’s no time left for

me to start, for me to live a life—

as if all the living I’ve done

til now was vanity,

as if the fact that there’s no knowing

when I end or how, only that I

will, is enough to stop hoping

for a future.

You ask only this of me:

to love you

to love others

to love myself;

but what if I

can’t love anything?

Would that break your heart?

Must it break your heart?

Will you ever speak again?

I’ve been white knuckling my faith

for so long that my hands are tired;

fingers twitch as my grip loosens

in despair. And it is then—

just then—that you finally speak

and I finally hear:

beloved, you say,

those who cling to their life will lose it,

but whoever loses their life for my sake

will find it.

So. I open my hands;

free fall into blessed nothing—

For my sake let me lose it; for your sake

let me lose it a thousand times.

Behind the Poet’s Pen: Kathryn H. Ross on Writing “For My Sake”

by Kathryn H. Ross

I’m a big believer in prewriting. Since learning the concept in my junior year of college, I’ve changed how I think about the lifespan of a piece of writing.

Is a poem born once the first or final draft is completed? Does the idea count as conception, or is the impetus of the idea the true moment of creation? How much does a changed draft change the piece, and once you’ve reached the final iteration, is that the child finally brought into the world?

Before I can answer any of these questions about the beginning of life, I have to stay grounded in prewriting, or in the context of this analogy, pre-birth. “For My Sake” was in the prewriting stage for the last eight years, though I wasn’t aware of that until last fall.

The contentious presidential election of 2016 ended on my 23rd birthday, and I think this was the day my poem entered pre-birth. I remember going to work and the first thing I saw was my boss crying. Social media was a wasteland of anxiety, arguments, and conspiracy theories about how bad the next four years would be for a variety of reasons. Reality was both close and far from these projections, and I personally remember being in a constant state of dread as I worried what new divisions would come next for a country that needed to heal.

What I didn’t expect was what happened to Christianity and all the ways people of every walk leaned into a fragmented faith, from the prosperity gospel to nationalism to a newfound doubt or unbelief. This fracture was only further exacerbated by the pandemic. I remember scrolling social media and seeing news reports of people refusing to wear masks or demanding others wear one in ways that only inflamed a time that was already sending people to rock bottom. Then there was the division over vaccines. I remember a video of an older woman giving an interview from her car saying that she needn’t wear a mask or get the vaccine because the “blood of Christ” covered her. On one side those who did wear masks or got vaccinated were all “living in fear,” “rejecting the gospel,” and “undermining Jesus.” On the other side, those who refused to wear a mask or become vaccinated were “asking for other people to die” or “ignorant and backwoods.” The country felt more callous and angrier than ever; everyone’s emotions were at their boiling point, and it all just seemed to get worse and worse.

People were so busy shouting each other down that they lost sight of the heart of God. And in the meantime, millions died. Most of them prematurely—and many of them alone.

As if this pain was not enough, mass shootings became more prevalent, and the country did the same thing: descended into circular conversations about thoughts, prayers, gun control, mental health, and why weapons were or weren’t the problem. Meanwhile, people died—far too many of them children. And as these bodies lay in their own blood, compassion was thin on the ground. Little could be spared for grieving parents, broken families, and traumatized citizens. Again, we were so busy shouting each other down that we were losing sight of God and goodness.

Maybe this is an oversimplification, but when someone is hurt, isn’t it more compassionate to give them the care they need than to immediately postulate about what caused the hurt?

Isn’t it a bit selfish and flawed to judge others in our own limited views, only to eventually conclude that it was the individual’s fault due to some shortcoming of their own? To conclude that if Black people just knew how to “act right,” they wouldn’t be persecuted? Or if queer people just weren’t “in everyone’s faces,” then no one would care about their lifestyle? Or if women would just “dress right” and stay modest, they wouldn’t even have to worry about assault? If people just “managed their money better,” they wouldn’t have financial hardships and end up on the streets.

On and on and on it goes.

This climate we’ve been living in for nearly a decade is distressing and exhausting, and I’ve often found myself wondering how any human being can justify, explain away, or condone the unnatural pain, assault, abuse, and death of another human being in any context. It’s a matter of erasing one’s humanity. It’s an evil that always goes too far. But what’s most disheartening is how often this behavior is carried out by the very people who should be most staunchly against it: self-professing Christians.

As I’ve lived through these last several years I keep coming back to one question: How is this happening?

And what I’ve come up with is that those who profess to love Jesus but spew hate or dissension do not know him like they should. They can’t. Because if they did, this would not be the world we live in. So, who or what are they actually believing in more? Perhaps those who have fallen away believe in a “Jesus” of their own creation, one who hates who they hate, loves what they love, enforces what they enforce, and never, ever wants them to be uncomfortable. A Jesus who cares about tradition, religion, and ritual, but not people unless they’re the right kind of people.

Weighed down by this thought, I was reminded of Matthew 10:39 and 16:25:

“Whoever finds their life will lose it, and whoever loses their life for my sake will find it.”

These words struck me with a deep revelation: It seems some misled Christians aren’t willing to lose the idols they’ve made of their lives and their religion. They are not willing to lose anything—their comfort, their ideology, their traditions, their self-righteousness, their views, or their understanding—for anyone. Not even for Jesus. And so, heartbroken and humbled, I wrote “For My Sake” as a response to this revelation and as a self-reflection.

I asked myself—honestly—what am I not willing to lose? What am I not willing to give away, not even to Jesus? I answered myself with another unexpected thing: my faith. I’ve been a Christ-follower my entire life. I’ve never been without Jesus in living memory and while that’s what I want for myself, I’m aware that that can be so dangerous if I don’t allow my faith to grow, change, doubt, and be threatened.

What does it mean if we hold on so tightly to our “religion” that we miss Jesus? Is this not the context of the gospels? Weren’t the Pharisees unwilling to give up their faith—their lives—for Jesus’ sake because He wasn’t what they thought or wanted or made them comfortable?

So, what do I believe about Jesus and Christianity that might actually be wrong? How might my beliefs actually be hurting people? And if He reveals these things to me, am I willing to let them go for his sake—and for mine? Because if I lose these things, don’t I become a better follower and a better person to do what he’s asked us to do: love God and love others?

“For My Sake” is really just a prayer. It’s me asking myself, and the reader, if we’re willing to truly lose our faith—that is, our beliefs, our very lives—for His sake? Because if we are, He tells us in no uncertain terms that whatever we lose for Him, we will find.

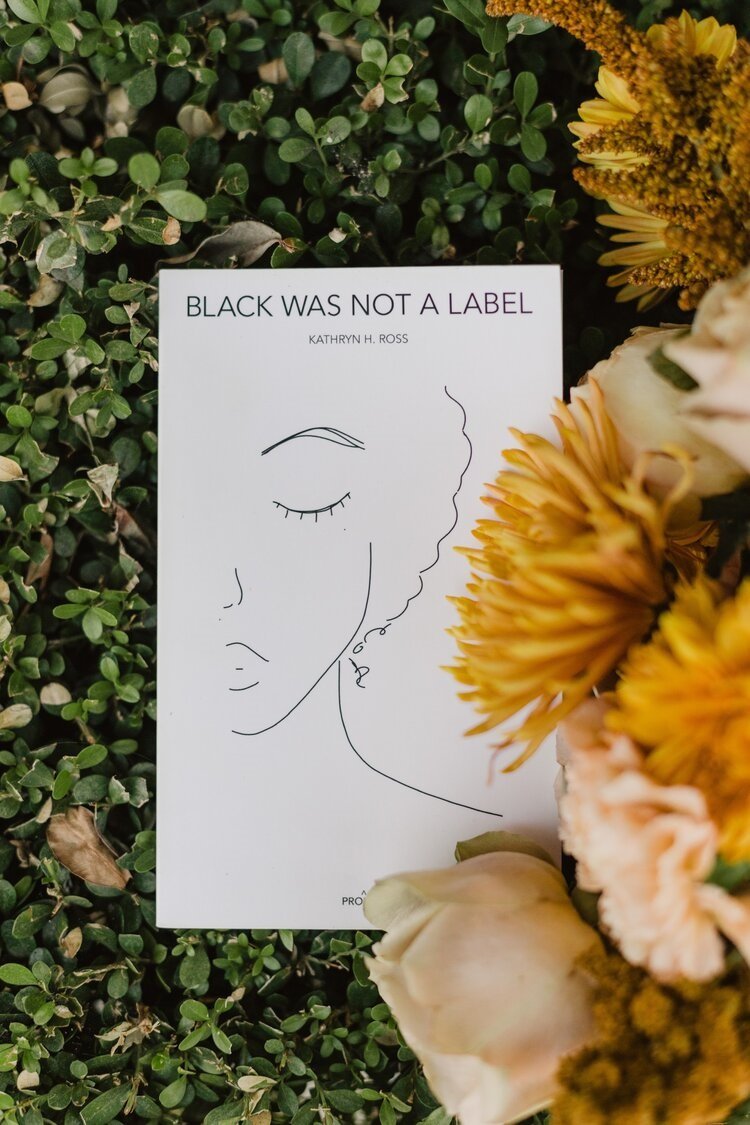

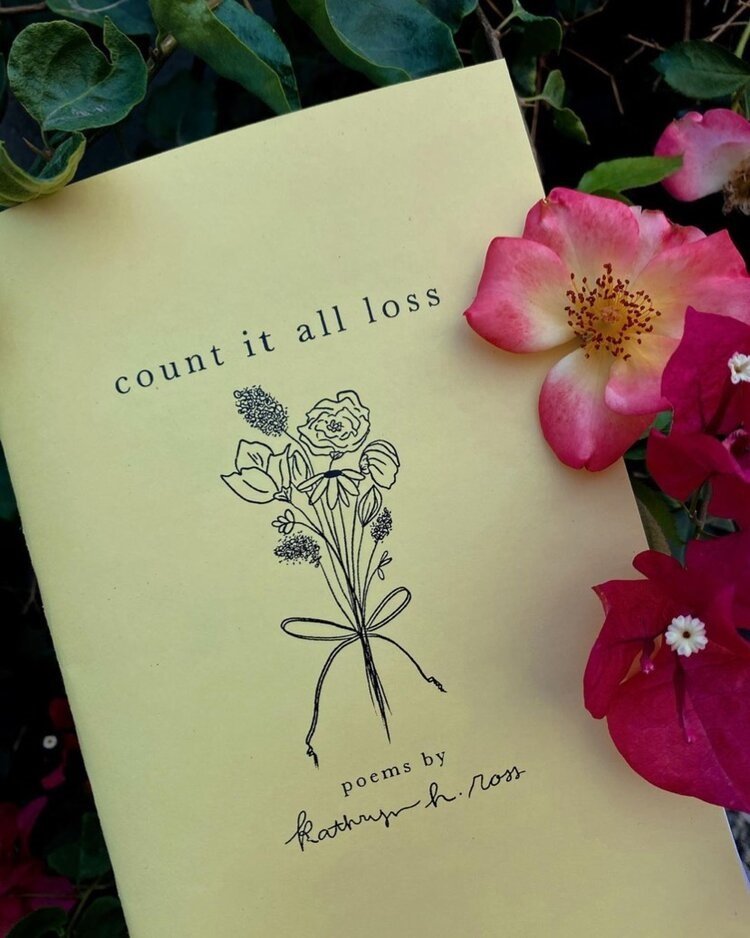

Visit Kathryn and buy her poetry collections here:

speak the write language.

KATHRYN H. ROSS

Kathryn is a SoCal-based writer. She is the author of Black Was Not A Label (PRONTO, 2019; Red Hen Press 2022), a collection of essays and poetry, and Count It All Loss (GoldScriptCo, 2021), a poetry chapbook. Learn more about her and read her other works at speakthewritelanguage.com.

You can connect with her and her lovely words on Instagram @speakthewritelanguage.